keyof, typeof and const assertions

This article will introduce you to typescript’s keyof, typeof keywords and the const assertion type. How to use these operators in day to day programming with typescript.

Typescript provides a great set of utility types,

operators and keywords that makes the lives of developers easier ✅.

In this article, we will take a look at and understand the typeof operator, index type query operator keyof,

const assertions and how to capture types from plain javascript literal values.

keyof operator

The keyof keyword is an indexed type query operator. It yields a union containing the possible property names/keys of its operand.

Most of the time, keyof precedes object literal types, especially user-defined types. It can be used against primitive types, however not very useful.

Syntax

keyof P

P = TypeAn indexed type query of type P or keyof P produces a union of property names for type T.

It is good to know how all types

behave and the yielded union when queried. Let’s take a peek at it, to avoid any surprises.

// Predefined Types

type KeyofAny = keyof any; // string | number | symbol 🤔

// You don't see these everyday 😬

type KeyofBoolean = keyof boolean; // "valueOf"

type KeyofString = keyof string; // number | "charAt" | ...Union of Object.getOwnPropertyNames(String.prototype)

type KeyofNumber = keyof number; // "toFixed" | ...Union of Object.getOwnPropertyNames(Number.prototype)

type KeyofSymbol = keyof symbol; // "toString" | "valueOf"

type KeyofVoid = keyof void; // never

type KeyofNull = keyof null; // never

type KeyofUndefined = keyof undefined; // never

//Enums

enum Preference {

TYPESCRIPT,

JAVASCRIPT,

}

type KeyofEnum = keyof Preference; // "toString" | "toFixed" ...Object.getOwnPropertyNames(Number.prototype)

// String literal type

type KeyofString = keyof 'Literal'; // Same as string. String literal types are subtypes of String primitive types.

// Array literal type

type KeyofArray = keyof []; // number | Union of Object.getOwnPropertyNames(Array.prototype)

//Tuple literal type

type KeyofTuple = keyof [number, number]; // number | number | Union of Object.getOwnPropertyNames(Array.prototype)

// Very important 🔥🔥!!

// object literal type

interface Rectangle {

type: 'Quadrilateral';

length: number;

width: number;

}

type keyofInterface = keyof Rectangle; // 'type' | 'length' | 'width'We will be focusing on the more useful object types from here on. The typescript playground is a great way to try these for yourself.

Usages

Correct use of keyof can reduce repetitive type definitions and make for elegant type definitions 🌹.

If you’re familiar with typescript’s utility types, you would have come across Omit. We won’t discuss what it does. But here is the definition from lib.es5.d.ts;

type Omit<T, K extends keyof any> = Pick<T, Exclude<keyof T, K>>;keyof any ? not shocking, is it? Now that we know the indexed type query of the predefined types 🙌🏽.

The expanded form of this expression keyof any is not hideously verbose, but you can just about see the elegance.

type Omit<T, K extends string | number | symbol> = Pick<T, Exclude<keyof T, K>>;We have a glimpse of elegant keyof usage, let’s talk about more practical use cases, shall we?

Typescript’s static compile-time type system closely models the dynamic run-time type system of JavaScript. For this reason, user-defined types are ”malleable”. It is common to take an existing type and make its properties optional and vice versa, create a subtype etc.

Below is a hypothetical function that inspects an axios request and returns a boolean for matched paths.

import { AxiosRequestConfig } from 'axios';

function isMatch(requestConfig: AxiosRequestConfig, path: string): boolean {

// object requestConfig.url is possibly undefined

return requestConfig.url.endsWith(path); //Ops

}

isMatch({}, '/users'); // Why is this okay axios :(Okay, let’s make sure our teammates provide a “valid” request configuration by reconstructing AxiosRequestConfig ! We want to keep everything but url.

import { AxiosRequestConfig } from 'axios';

// we obtain all permitted property names with `keyof` and exclude the url property name

type ConfigKeys = Exclude<keyof AxiosRequestConfig, 'url'>; // Great url is gone

// lets reconstruct now 🔨

type CustomRequestConfiguration = {

url: string;

} & { [property in ConfigKeys]: AxiosRequestConfig[property] };

function isMatch(

requestConfig: CustomRequestConfiguration,

path: string,

): boolean {

return requestConfig.url.endsWith(path); // Everyone is happy

}

isMatch({}, '/users'); // No !

isMatch({ url: 'https://mrgregory.dev/users' }, '/users'); // Okay we are friends now !Imagine having to type all the other property names and respective values to make this possible, keyof to the rescue.

If you are unfamiliar with &, it is called the intersection type operator, say object.assign() 😄.

AxiosRequestConfig[property] spooky ey ? This is call indexed access or lookup types,

similar to querying an object literal, it returns the property value. We will dissect this further down. Stay put.

Let’s look at another example.

Take this hypothetical register form with a “tonne” of fields. We are required to validate and track errors for each field!

Equipped with keyof;

interface FormFields {

firstName: string;

lastName: string;

email: string;

password: string;

birthDay: string;

birthMonth: string;

birthYear: string;

consented: boolean;

confirmationPassword: string;

}

// Create a union of string literal types

type FieldNames = keyof FormFields; // "firstName" | "lastName" .... | "consented"

type FieldErrors = { [field in FieldNames]: boolean }; // { firstName: boolean; lastName: boolean; .... consented: boolean; }Elegant, isn’t it? We do not have to maintain separate explicit types for formFields and FieldErrors. Great first step!

Another example

Very recently I learnt about the power of JSON.stringify replacer function.

Let’s create a type-safe half baked JSON.stringify that accepts an object with a very specific shape, whose values are only primitives 😄 to keep it simple.

declare function stringify<Input extends object>(

source: Input,

replacer?: (

key: keyof Input,

value: Input[keyof Input],

) => string | boolean | number,

spacer?: string | number,

): string;

interface Person {

name: string;

age: number;

beard: boolean;

}

const pawel: Person = { name: 'Pawel', age: 1, beard: true };

// ok

stringify(pawel, (key, value) => (key === 'age' ? 23 : value));

// ops Error, this condition will always return 'false'

// since the types '"name" | "age" | "beard"' and '"height"' have no overlap.

stringify(pawel, (key, value) => (key === 'height' ? 23 : value));

// Error {} is not assignable to `string | number | boolean`

stringify(pawel, (key, value) => (key === 'age' ? {} : value));Here, we see the indexed access query in use to make sure value is one of the user-defined property value types. Let’s shine some light on how keyof works in lookup types.

interface Person {

name: string;

age: number;

beard: boolean;

}

type Values = Person[keyof Person]; // string | number | boolean

// How ?

// Person[keyof Person] =

// Person["name" | "age" | "beard" ] =

// Person["name"] | Person["age"] | Person["beard"] = string | boolean | number;We will see a few more use cases of keyof in the next section while we discuss typeof

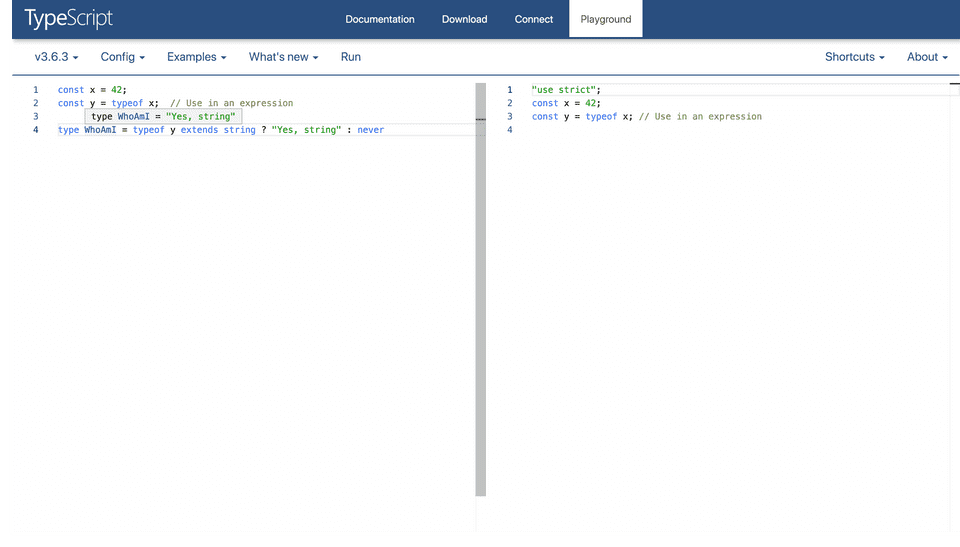

Typeof operator

The typeof keyword can be used in an expression or in a type query. When used in an expression,

the type of the expression will be a string thus the string primitive type of the evaluation of the expression.

The dual and more useful of this is type querying with typeof which we will see a bit later.

const x = 42;

const y = typeof x; // Use in an expression‘x’ in the example above has the type ‘number’ and ‘y’ has an implicit type ‘string’. Read this as y is the typeof (typeof x) and you see the light 💡 😄.

Here we validate if y is indeed of type string obtained from the expression typeof x, which evaluates to a string primitive type "number". Got it?

Javascript’s typeof Operator

typeof undefined; // "undefined"

typeof true; // "boolean"

typeof 1337; // "number"

typeof 'foo'; // "string"

typeof {}; // "object"

typeof Number.parseInt; // "function"

typeof Symbol(); // "symbol"Typescript’s typeof Operator

typeof operator shines more when used as a type query operator. You can query literal values for type or shape.

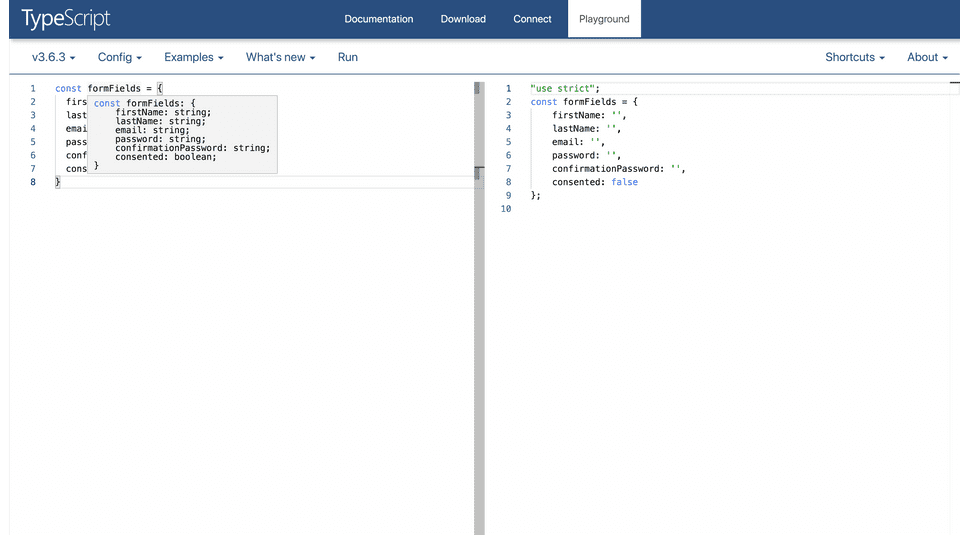

Let’s go back to our register form example. We defined an object literal type via the interface FormFields, but we can take this a step further.

Later down the line, we would have had to define an object literal to hold the default values for our hypothetical form.

interface FormFields {

firstName: string;

lastName: string;

email: string;

password: string;

birthDay: string;

birthMonth: string;

birthYear: string;

consented: boolean;

confirmationPassword: string;

}

type FieldNames = keyof FormFields;

type FieldErrors = { [field in FieldNames]: boolean };

const defaultFormFieldValues: FormFields = {

firstName: '',

lastName: '',

//....

}

const defaultFieldErrors = { //.... }What we have done here is introduced more maintenance work. If I added a new field to our form, I’d have to remember to update

all defined types and interfaces ☹️. Let’s do better with type querying.

const formFields = {

firstName: '',

lastName: '',

email: '',

password: '',

confirmationPassword: '',

consented: false,

};

type FormFields = typeof formFields; // { firstName: string; lastName: string; ... consented: boolean}

type FieldErrors = Record<keyof FormFields, boolean>; // { firstName: boolean; ... consented: boolean}

declare function useState<T>(defaultState: T);

function RegisterForm() {

const [formFields, setFormFields] = useState<FormFields>(formFields);

//...

}The captured types are widened and can be used just like any user-defined interface or type.

Note: Most of the time, typescript will infer the types of javascript literals. The inferred type is widened.

Another common place you will find this operator is in mapped types, especially useful for type transformations. Let’s make our form field type have only readonly properties !

const formFields = {

firstName: '',

lastName: '',

email: '',

password: '',

confirmationPassword: '',

consented: false,

};

type LooseFormFields = typeof formFields;

type FormFields = {

readonly [property in keyof LooseFormFields]: LooseFormFields[property]

}; // { readonly firstName: string ... }Typescript provides a built-in utility for this purpose called Readonly.

declare let formFields;

type FormFields = Readonly<typeof formFields>;Capturing literal type with const assertions

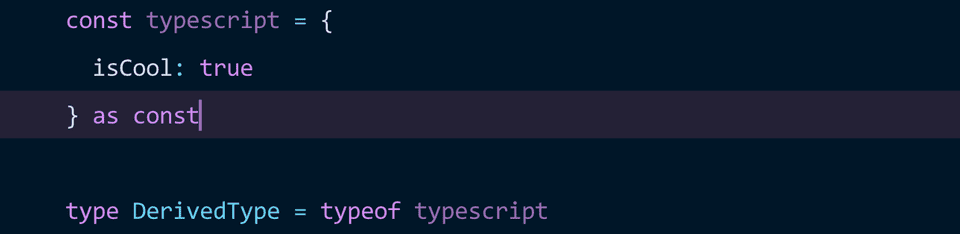

TypeScript 3.4 introduces a new postfix operator for literal values called const assertions. In summary, it prevents literal type widening,

makes object and array literal properties become readonly. These characteristics make it ideal for capturing and narrowing types.

We will focus more on the use of const assertions with object literal types. If you want to capture a literal primitives types use a const declaration.

// typeof a is the literal type 42 and cannot be widened.

const a = 42;

// This is quite redundant as it is indicative that b cannot be reassigned and or widened ❌

// This is not idiomatic javascript

// for semantic clarity use a const declaration

let b = 'Hello' as const;

b = 'Hi'; // NopeWith object literals;

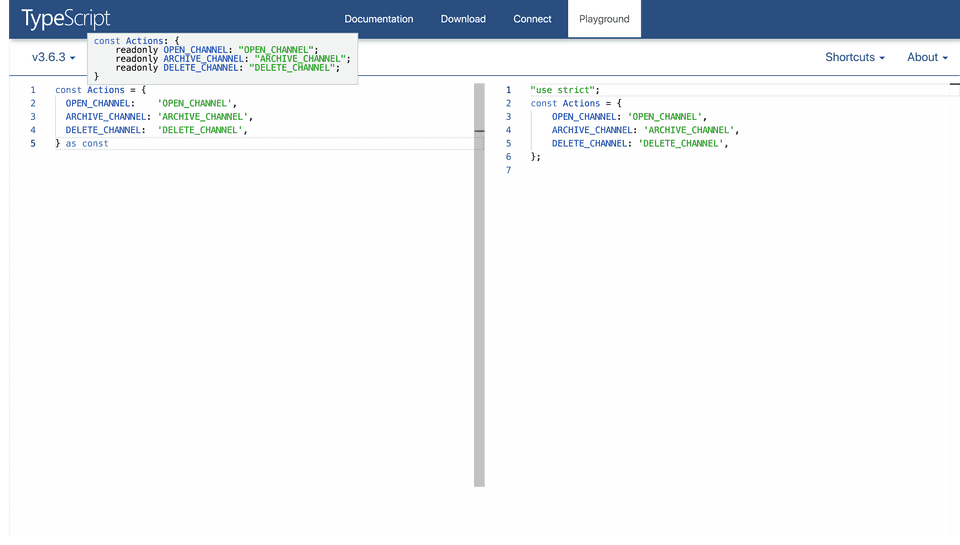

const assertions are perhaps most useful for creating narrowed and enum-like literal types. The example below demonstrates these.

declare let fs: any;

const flags = [

{action: 'delete', files: [ 'Pedro.txt', 'Sharkey.txt' ] },

{action: 'create', file: 'Dan.txt' },

] as const;

for (const flag of flags) {

if(flag.action === 'create') {

// sweet sweet narrowing

fs.writeFileSync(flag.file)

fs.writeFileSync(flag.files) // Error, Did you mean 'files'.

}

}

}enum-like constructs

const NOTIFICATIONPREFERENCE = {

email: 'EMAIL',

text: 'TEXT',

both: 'BOTH'

} as const

NOTIFICATIONPREFERENCE.email // ok

NOTIFICATIONPREFERENCE.test // ❌

// Property 'test' does not exist on type '{ readonly email: "EMAIL"; readonly text: "TEXT"; readonly both: "BOTH"; }'.

// Did you mean 'text' ? ✅ Beautiful, isn’t it?

If you made it to this point, you would have had an idea how to use keyof typeof and const assertions in your day to day programming

with typescript. If you know something that wasn’t mentioned in this article, I’d love to know them too. Please share in the comment section below!

Until next time, stay curious!